I am not a circumpolar lumberjack. Neither my first trade nor my second trade – nor any professional trade that I have pursued – has been in the logging industry.

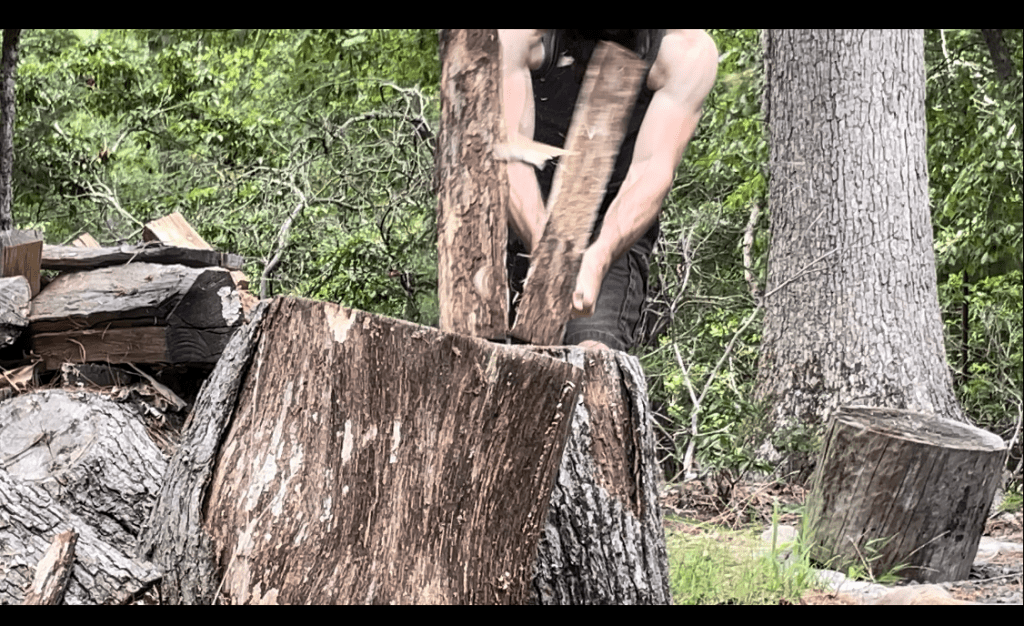

But I still have taken down my share of trees and split my share of firewood.

For that, an ax is man’s best friend, and when it comes to doing just about anything with an ax, the best one I’ve ever handled is a Cold Steel Trail Boss.

It’s highly generalized, and there are way better axes out there, but when you consider the features, the quality, the price, and the downright usability, I think it might bring the most value, all things considered.

It’s not the best felling ax, but it’s good. And it’s not objectively a good splitter, but for its weight and dimensions, I think it’s excellent. It can do a little of everything, exhibits impressive quality, and most importantly, if you know where and when to shop for one, you can probably find one, still, for about $22.

No other ax in this price range, that I have seen, anywhere, comes close. Not even the cheap hardware store axes that aren’t worth using as props in cheap photoshoots for retail ad catalogs.

They’re more expensive and inferior, and that’s damning.

So before I digress too drastically, let’s pick apart what this ax is and why it’s so great.

And, for the record, I bought 4 of them and then another that I offered as a gift to someone else.

Cold Steel Trail Boss Specs

Let’s get the boring stuff out of the way – the specs.

The Cold Steel Trail Boss is a pretty nondescript ax, in terms of aesthetics. Nothing about it is particularly eye-catching, which is quite alright by me because I appreciate utility first in a tool, and looks second.

The Cold Steel Trail Boss is 27” overall in length and sports an American hickory haft (which itself is 27”).

It has a 1055 carbon steel head (more on that below) in what Cold Steel calls a “European pattern.” I would call this a German felling pattern, similar to what Prandi uses in many of its axes. This makes sense, since Prandi actually is a European producer of bladed tools. (Again, more below).The head is partially coated with thick, corrosion-bucking black paint. The cheeks and bit are left bare.

The poll is flat and the bit flared, with 4.5 inches of cutting edge. The grind starts flat on the cheeks but finishes in a convex configuration. This allows a user to finish a very sharp ax. One of my Trail Boss axes is almost sharp enough to sharp hair.

The tool weighs 2lbs, 9.5 ounces overall, which is pretty light considering the size of the ax. It is really well balanced, light enough to use for carving with one hand, and heavy enough to swing with both with the intent of felling larger trees.

Blade Steel and Pattern

Cold Steel has been judicious about labeling the type of steel it uses in this ax. I don’t have to guess like I did with my Cold Steel Special Forces Shovel – although I think they both use the same steel, which is 1055.

There are only two ingredients that really matter in 1055 steel: carbon and iron, which are the two elements that constitute steel anyway. The “1055” designation tells you what you need to know. This steel is .55% carbon, or between .5% and .6%.

This is often labeled as a “high-carbon steel” but the reality of the situation is that it is fairly low carbon. Before you cry foul, in an ax this is actually generally a very good thing.

The higher the carbon content in steel (generally speaking) the more brittle it is. This will also be influenced by the formation of carbides in the alloy matrix that arises from the other chemical additives in the steel, as well as what sort of heat treatment the steel has been given. However, as a general rule, the more carbon, the harder the steel will be.

In some tools, like files and short-bladed knives, hardness is a benefit. However, in striking tools, it can be less than a good thing. It’s easy to fix a dulled, blunted, or rolled edge, but if the ax bit chips or the head shatters, you’re up a creek and need either to buy a new ax or become a blacksmith.

This alloy, with its relatively low concentration of carbon in the mix, is significantly tougher than other steels that have more carbon, like 1095, for example. It’s much less likely to shatter, chip or break. A concentration of .95% carbon might be a good thing for a knife, but for an ax, it’s not necessarily beneficial.

I have heard that some smiths and toolmakers create a differential temper. In an ax head, this would consist of giving the bit a more aggressive heat treatment than the poll. This would make the edge last longer without putting the entire tool head at risk of breaking. This also gives the advantage of creating a softer poll that can be used as a hammer or maul without too much risk of cracking the head.

I’m not sure if Cold Steel has done this and I haven’t performed any specific tests to determine how long the edge lasts, but I know two things. One is that with little work I can get the bit almost sharp enough to shave with. The other is that it won’t hold that edge for long, even using it on soft wood like pine. One errant strike into sandy soil (which I have unfortunately done many times) and your edge will still be sharp, but it won’t be what it was.

What I can say is that, even without knowing specifically what sort of heat treatment Cold Steel has given this ax, the head is hard enough to take a really good edge but not so hard that it’s likely to chip or break. If it were, I would have done so.

Now let’s talk a little bit about the pattern that Cold Steel has used for this ax. They call it a European pattern. It has a gracefully curved bit that offers 4.5 adequate inches of cutting length. The toe is flared up slightly, and the heel sweeps gracefully down away from the cheeks. It’s certainly not bearded, but the heel is long enough that you can choke your hand up under the head and use this as a carving ax

I’ve also heard this pattern referred to as a German pattern. I’m not entirely sure about this but if I recall correctly that’s what Prandi calls it, and they actually make axes in Europe. It’s also similar to a pattern produced by Adler, which also makes its axes in Europe – in Germany, actually.

Whatever you call it, the pattern stands on its own merits. Generally speaking, ax patterns can be used for a few different things. Hewing, carving, splitting, and making broad crossgrain cuts that are effective for felling and bucking. This ax falls into the latter camp. This pattern is exceptionally effective at making broad, deep cuts across the grain of a tree or a piece of wood – but I’ll expound on that below.

Depending on how sharp you make the edge, you can use this ax for carving as well. The weight of the head is not unwieldy, but the balance is thrown off a little by the weight and length of the haft, but again, more on that below.

The slightly flared up toe also makes it possible to make fairly detailed cuts with this ax. Nothing like what you can do with a knife, but not too bad. If this was the only piece of steel you had with you in the woods or in the yard, you could do much worse.

Wedge Configuration: Cold Steel Uses Dual Round Safety Wedges

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite aspects of this ax, which is, admittedly, almost unnoticeable unless you’re specifically looking for it.

Before we get into grain orientation, I want to address how Cold Steel has hung this ax head on the haft. The basic method for fixing a tool head on a wooden handle is to make a transverse cut across the top of the haft – the part that will be forced through the eye of the tool.

The head is slipped onto the haft, and then a wooden wedge is driven into the cut that transects the haft through the eye of the tool. Once this is driven in, the custom is to drive another wedge across the wooden wedge. Driving this down to the level of the eye, wood is displaced within the eye of the tool, again the metal. This holds the head of the tool on the haft – with several thousand pounds of force, or so I have read.

Now, there is a special type of wedge that displaces more wood against the sides of the tool’s eye, and more effectively than a flat steel wedge. It is called a circular wedge, or a round wedge. It looks like a small steel cylinder. If you look through the eye of a tool’s head, it looks like a circle of steel.

Now, taking a look at the top of the eye at the top of the head of the Trail Boss, we can see now one but two steel safety wedges.

Cold Steel has done wonders affixing the head of this ax to the haft, and it takes a force of God to remove the head from the haft. I know, because I have done it when replacing tool handles. I had to use a steel punch and a maul just to get the remnants of the haft out. This thing is seriously secured very w

The reason I consider this such a big deal is because this is such an affordable ax. I’ve seen other axes that are cheaper which are hung with only one wooden wedge and no steel safety wedge at all. This works, but it doesn’t provide the same quality or security as when you use a steel wedge. One circular wedge is an improvement, two are a redundant safeguard. If you’ve ever heard “two is one and one is none,” here is a nice example of that.

The circular wedge displaces more wood than a straight wedge, and two of them are even more impressive. This is just one of the small details that I really appreciate about this ax. So now we can talk a little bit about grain orientation and quality of the haft.

Haft Material, Ergonomics, Grain Orientation

Haft material and grain orientation are two big sticking points with commercial axes – especially cheap “hardware store” axes. This is because, for whatever reason, the quality of handle grain orientation has seriously tanked. Not that I remember “when it was good” but I can say that I’ve more than once had to ask employees at hardware stores to pull out overstock so I could assess the grain of replacement handles. There’s no point in replacing a broken handle with a piece of garbage with poor grain orientation that will break on your inaugural swing. I learned this the hard way with my 8 pound sledgehammer and I won’t make that mistake again.

When you’re looking at a tool handle, regardless of what type of wood the handle uses, the grain should be aligned front to back, with the layers of wood arranged lengthwise as shown in the picture below.

What you don’t want is a handle with grain that looks like it does in the picture below. When the grain is arranged like this, the handle is likely to break. Fortunately, as shown in the picture below it is somewhat acceptable as the handle below is for a small tool that doesn’t experience a lot of stress. Still, it’s terrible grain orientation.

The reason it’s such a problem is because when grain is arranged like this, and the tool is swung or stressed, it experiences a lot of shear force. Too much, and the fibers will separate along the grain, creating a crack that travels the length of the tool handle. In essence, the handle will break.

It’s also no good when a tool handle has grain orientation that looks like the picture below.

This is not as bad as the previous image, but the fibers still can’t take advantage of the full strength of the wood, and are likely to split or crack.

Another thing you want to look out for is called run-out. Run out occurs when a portion of the grain is exposed at the side of a tool handle. This is a weak point and an area where separation of the fibers is likely to occur. If breakage occurs, it is very likely to occur at a place on the handle where there is run-out.

You also want to look out for knots. Knots are not quite the same as run-out, but they do weaken the overall strength of the tool handle and breakage is likely to occur at locations where there are knots – or near them.

Now let’s get back onto the topic of the Cold Steel Trail Boss. I’m not sure if there are any retail outlets in the country where you can buy this ax. I’ve bought all of mine online. Buying an ax or any tool with a wood handle online is a crap shoot because you can’t inspect the tool handle beforehand. Whenever I buy anything with a wood handle, I always closely inspect the tool to make sure the grain orientation is suitable, there are neither knots nor run out, and that otherwise the grain looks tight and straight.

Naturally, you can’t do this online, but I figured that the $23 price tag was worth the price of the naked head. If I got an ax with a horrible handle and broke it on the first swing, I’d still get my money’s worth replacing the handle.

It wasn’t even that bad, honestly. This is a picture of the first Cold Steel Trail Boss that I bought, back in 2017 or so.

As you can see, the grain orientation isn’t perfect, but it’s pretty good. It’s straight, tight, and there’s basically no run out. I’ve seen better handles, but it’s pretty good.

Now let’s take a look at the one I primarily use.

The grain orientation is actually inferior to the first one I got, but it’s pretty good. And let me tell you what, despite the fact that this one has worse grain orientation, nothing’s gone wrong with it. And I’ve given it reason to, trust me. This ax has been dropped, errantly struck into earth, even hit the odd rock. Also, I’ve had some pretty dreadful overstrikes and there’s never been a collar on this ax. Some of them were so bad that the strikes compressed the grain at the throat of the ax. You can see the damage here.

Nonetheless, despite all those odd hits and strikes, and despite the less than perfect handle, the ax haft hasn’t cracked or split. I think that’s saying something. I know it will happen eventually, and I’m already ready with a replacement handle.

Still, for now, the haft is holding up and I keep going. It’s split through quite a few cords of wood, taken down and processed a few small trees, and it’s going strong.

Now there’s one more thing I want to address before we get into handling, balance, and whatnot. The wood that Cold Steel says they use is hickory. I’ll admit that I can’t tell from looking at it that it’s hickory, but I’ll take Cold Steel’s word for it.

Here’s what I can say. The haft is stamped “Genuine Hickory,”

The grain is good, the wood is dense and strong, and that’s that. It comes with some sort of varnish or clear coat that you might want to take off – I treat mine with beeswax and grapeseed oil – but that’s a matter of preference.

Handling, Weight, Balance

You already know the weight of the ax since I generously divulged that earlier in this post – but the way an ax is hung, the thickness of the handle, and its other dimensions can make a huge impact on how much it feels like it weighs. It’ll also affect the handling and balance overall.

What can I say except that this ax has excellent balance and handling. I’m not quite sure where to start, even. I can say, however, that my experience has been positive overall. There’s only one thing I’d really change about this ax, honestly.

This ax has really good ergonomics and indexes normally. Some axes are made with thick, round handles that don’t index. Others are made with deceptively thin handles that are uncomfortable to handle and want to slip out of your grip. Others have bumpy hafts. This ax has none of those faults.

There are no bumps or faults in this ax haft, not that I can feel, at least. It feels perfectly smooth in the grip. Also, the ax haft has a somewhat ovoid cross-sectional profile that enables it to index well and prevents it from wanting to rotate in your grip. Even if you strike a hard glancing blow, it’s hard to lose control of the ax – at least, that’s how I feel.

The end of the haft has a generous swell that’s perfectly contoured. As in, it’s not just a round knob like the base of a bat has. This haft is contoured so that you can place your non-dominant hand on it and perfectly control the motion and force of the ax, without feeling like your hand is going to slip off it. That would be very difficult, thanks to the profile, thickness, and width of the knob at the base of the haft.

With your dominant hand at the throat of the ax and your non-dominant hand on the knob, this ax is very easy to control. Also, with both hands on the knob, you can still control it pretty well even though it admittedly takes a bit more strength.

That said, this ax is in the sweet spot. At under three pounds, and at this length, it’s still pretty easy to control with both hands at the base of the haft. Harder, but doable. You can’t do that with a maul or a full size felling ax (above 3 pounds) unless you have the brawn of a bodybuilder.

It’s not particularly easy to wield this ax with one hand like a hatchet or a tomahawk, but I’d say it could be done. You need to choke up and it gets pretty tiring, but it could be done. That said, it’s light enough that you can wield it with two hands for hours without getting fatigued.

Balance, like indexing, is really good. I haven’t officially measured it but I’d say it’s just a little bit up the midway point of the haft towards the head. This makes it very easy to swing this axe with force, but with precision. The more head-heavy an ax is, the harder you can swing it, but the harder it is to control it with great precision. This ax is in the perfect middle ground – weighted to make deep incisive cuts, but light enough that you can swing it like a tack driver.

All in all, it has excellent balance, handling, and ergonomics.

Now for the one thing that I’d change about this ax: the length, but I must make this statement with a caveat – the length.

Now, I think this ax could benefit from another two to three inches on the haft. That would substantially change the balance point and the longer handle would make it easier to swing the ax with full power. The extra length would also give the ax greater reach, which would diminish the incidence of over strikes, which are a potential danger to this ax, since it’s so short (it can be hard to estimate where it will fall before you’re used to swinging it).

Now, I got pretty used to this ax so I no longer have any qualms about the length. But I can also say this.

This is designed as a pack ax, and if I’m being honest I feel like it’s on the longer end of the spectrum for a pack ax. Adding length to the design would come with benefits, but it would fundamentally change the handling, balance and weight.

It also would make it more difficult to carry by lashing it to a pack.

Originally, I would have appreciated a few more inches, but at this point, I think I see the advantage of the shorter length.

All things considered, this ax swings and bites like a felling ax a full pound heavier, but has the handling of a tomahawk. I’m no professional logger but even I know that’s a rare thing.

Felling, Cross-Grain Cuts

The Cold Steel Trail Boss does a lot of things really well, but there is nothing it excels at like it excels at all sorts of cross grain cuts, which includes both felling trees and bucking logs. You’ll be amazed at the efficiency with which this ax can take a bite out of wood. I’ve seriously sunk this bit across the grain of softwoods (like pine) up to four inches at a swing, and that’s not an exaggeration. It won’t happen with every swing, all of the time, but when you angle it right and deliver the proper force, this thing really bites.

It’s equal parts blade profile, head weight, haft length, and grind, and, to be honest, nothing about this observation is surprising since this is a felling ax. It should be good at making cuts across the grain of wood. Well, it is, so Cold Steel, consider that a job well done.

The blade profile, a German or European pattern, has a long, wide, curved bit that is perfect for taking chunks out of wood at both steep and shallow angles. Combined with the adequate weight of the head and the length of the handle, you have a recipe for a serious felling pattern.

But the Cold Steel Trail Boss has something else really important going for it that a lot of other axes don’t even other felling patterns that I’ve handled. It has to do with the grind and orientation of the ax’s cheeks.

First, most felling axes have a prominent convex grind. This is actually a good thing, in a way, because it strengthens the bit of the ax against impact, making it very difficult to roll the edge and nearly impossible to chip. Even on contact with stone or other hard impediments, you’re likely just to compress or flatten the edge rather than chipping it.

However, a convex grind does not bite the same way a flat or hollow grind does. The problem is that both flat and hollow grinds are not suitable for making axes because they are weaker and not well suited to the striking stresses that ax heads customarily endure.

Cold Steel does use a convex grind, but it’s not aggressive at all. Truth be told, the grind of this ax is actually more or less flat. It’s not really noticeably convex until you get right up to the edge. Up to that point, it’s a very shallow flat profile – that dives really deep into whatever you’re cutting.

That’s the other thing – the angle of the cheeks. While most felling axes are flat cheeked, some of them are pretty obtuse. Just like any wedge, the wider it is, the more force it takes to force it between the layers of whatever it is you’re cutting.

Well, you don’t have to experience that problem with the Trail Boss, because the grind is so narrow. This thing, though thicker and heavier than a knife, is ground almost like one. Combine that thin edge and thin grind and you have a recipe for an ax that cuts like a razor – and it does. I actually sharpened one of these things to the point that I could almost shave the hairs on my arm.

Let me tell you, this thing cuts. The edge could use a little work from the factory, but as a felling pattern, there’s really not much you could do to improve the design, especially not at this length, weight and price point.

Limbing

Pretty much all of the things that make for a good felling ax also make for a good felling ax also make for a good limbing ax. I’ve struck this thing through 2 inch pine boughs with one swing before, and on an angle, that’s a traversal of more than 3 inches of wood.

Needless to say, lighter, nimbler axes are better for limbing because you can control them with the confidence and precision that limbing requires. Well, all of the things I have painstakingly belabored so far in this article are a credit to its limbing abilities. I only wish I could show you in real time how effective this thing is at cleaving limbs from a trunk.

It’s going to sound like an exaggeration, but I can honestly say that using it to limb fallen trees is actually so gratifying that you won’t want to use a saw again, seriously. It’s faster, more efficient, and so much more fun.

I actually give this thing higher marks as a limber as I give it for felling. It probably does this best of all.

Carving

Now for what you might consider a bit of a disappointment. Considering all of the laudatory remarks I’ve hurled at this ax, you might be expecting me to say it makes a fantastic carving ax. It really doesn’t.

It works, but there are a few things that work against it as a carving ax. One is the weight of the ax. It’s honestly just a little bit too heavy to comfortably wield with the dexterity required for carving.

Just look at the picture above. You can see that you can choke up on it and use it with careful poise, but it’s just not particularly easy to do. The one benefit of this ax as a carver is the fact that you can get your hand up under the bit at the throat of the ax so your hand is directly behind the cutting edge. That gives you great control, but again, the head is just too heavy.

Here’s the other thing. A carving ax should have a very narrow grind and you should take the bit down to the point that you could shave with it – literally. Think about your other wood-carving tools. If they’re not hair-popping sharp, you’re doing something wrong.

Now, don’t get me wrong, you can make this ax that sharp, but it takes a lot of work, and the second you go back to felling or splitting, you’re going to blunt it down. So you’re kind of working against yourself if you do.

The other thing is the length of the handle. A carving ax should have a short handle because that makes it so much easier to control with one hand. Using this ax with one hand is just annoying because the haft tends to smack you in the ribs or get in your way as you attempt to manipulate the ax with any semblance of deftness.

So, to reiterate, it’s an alright carving ax – but not great.

Splitting

I’m split on this ax as a splitting tool.

Ha ha.

But seriously, I’m not sure how to weigh in on it, in the spirit of fairness. It’s going to take a lot of explanation to get to the heart of the matter.

Objectively, it is not a good splitter. It is too light, too short, and overall too small. The pattern, which is designed for felling, is too narrow. It tends to bite into wood and then bind terribly, especially if you sink it into a round that’s just too big for it. I’ve had to use wedges and gluts to free this ax from oak and maple rounds on numerous occasions.

It’s also not heavy enough to sell itself as a splitting ax. Even a strong guy can’t put enough energy in the ax head to make it a maul. You can drive this thing through firewood, but using strength to overcompensate for a bad design is burning energy. What’s that they say about working smart and instead of hard? I forgot because I’ve been using a felling ax as a splitter for too long, I guess, but you might remember.

Length is also working against the Cold Steel Trail Boss here, because you can’t drive a lot of power through it to swing it like a maul, a sledgehammer or a splitting ax. It’s light, it feels light, and that makes it sub-par as a splitter, especially when you compare it alongside tools that are designed for the job.

But that is not fair, and it does not do the ax justice whatsoever.

We need to take this in context and look at it with the advantage of the proper perspective. This ax is not a splitting ax, nor was it in any way designed to be. Some might say the very act of using this ax as a splitter would be tool abuse.

They wouldn’t be wrong, and I’m saying that in honest fairness.

But here’s the thing. While this ax is objectively not a good splitting implement, it is an amazing splitter considering the class it occupies. It’s a sub-30-inch pack ax that weighs less than 3 pounds.

Splitting with this ax is like using a 4-foot ultralight rod to cast a 2-ounce spoon. It would be pretty impressive if it could, wouldn’t it?

That’s what I’m talking about here.

I have split cords and cords of wood with this ax. I’ve used the Cold Steel Trail Boss to quarter everything from pine and spruce to white oak and red maple, so it’s seen its share of tough, hard wood, even some knotty, curly grained nonsense that was not fun to split.

And it has never flinched. It bites deep and has flat cheeks, so yeah, on quite a few occasions I’ve gotten this thing to bind, and it’s taken some serious creativity to get it out. On more than one occasion I had to use a wedge or two to free it. But always come back up swinging.

Is it particularly efficient at splitting? Well, when comparing it to a maul, a sledge and wedge, or even a heavier felling ax, no, I can’t really say that it is.

But it flies through light wood with straight grain. I daresay it’s good at splitting pine and other light wood. Using a few splitting tricks, I can even power it through oak, too.

Am I putting more power behind each stroke, and working harder to make up for the light weight and design of the ax? Absolutely, I am. But the following are also true: the ax, being light, doesn’t tire me out as much. I can swing it for a long time, and as long as I don’t burn too much energy freeing a bound-up ax, it’s pretty solid.

Actually, all things considered, that’s what’s the most aggravating thing about using this ax as a splitter. As I said, it binds pretty frequently and I need to burn energy getting it out. On those few splitting sessions where that didn’t happen (or happened minimally) it was pretty enjoyable to use.

So, to recap, this is not a particularly efficient splitting ax, mostly because it is not a splitting ax at all.

Then again, if you consider its proficiency as a splitter taking that into account, it’s better than good – it’s great.

Hewing

The same things that make this ax somewhat less than practical as a carving ax are also a crutch when it comes to hewing.

However, there is one thing I can say about this ax as a hewing machine: it’s better for hewing than it is for carving.

It’s still irritating to use with one hand and the haft gets in the way. That said, as I have said so many times in this post already, this ax bites deep, which makes it very efficient for hewing. A 45-degree angle and a sharp tap can put a deep gash across the grain of a wood blank. Turn the thing over and repeat the process on the other side, and you can shave an inch off of whatever piece of wood you’re working on without too much effort.

Hewing doesn’t quite require the same razor sharp edge that carving does, and it benefits from a little more muscle, which you can put behind a head that’s heavy like that. Now, that’s for hewing small blanks. I can’t say I’ve ever used it to hew full size boards the old-fashioned way, standing on the plank. I can only imagine this ax is nearly as efficient as a broadax, but for the fact that it’s a little lighter and shorter.

So, take that for what it’s worth, this ax is a decent hewer – better than a carver. Also, spend some time sharpening a saw and you’ll be a lot more willing to use an ax like this for hewing, that much is for sure.

Debarking/Fleshing/Scraping

A bearded ax with a longer, wider bit would be more efficient for debarking, fleshing, or scraping. That said, the Cold Steel Trail Boss is relatively serviceable in this arena.

Choking up under the head, as you would if you were to use it for carving, you can use it for scraping, fleshing, or debarking. You can also use it sort of like an ulu for making wide, sweeping cuts.

If you put the right edge on the ax, which isn’t too hard, as I have mentioned you can use it to make push cuts and even pull cuts. This makes it pretty useful for removing bark from trees, such as separating the bark from a cedar log for the purpose of making cordage.

It’s a bit of a stretch, and purpose-designed draw knives (not to mention regular knives) are far better adapted to the task. But, the thin flat grind of the Cold Steel Trail Boss makes it work, at the very least.

Piercing

Piercing is not a task you typically think of associating with asks, despite the fact that there are so many camp chores (and general tasks) that require a piercing point, ranging from the ability to drill holes through wood to the ability to put a new hole in your belt.

Axes are not generally good for this. Yankee and Jersey patterns, which are pretty common in hardware stores and most commercially available axes, are all but pointless for piercing. I mean, they are literally pointless.

If you’re going to use an ax for piercing, you either need a spike tomahawk or maybe a Pulaski ax with a mattock or a pick in lieu of a poll. Sometimes bearded axes have a bit of a toe that you can use for piercing, but that’s pushing it.

Well, this ax isn’t great for it, either, but it’s not terrible either. The toe of the ax, as is customary on European patterned axes like this, is slightly upturned. This makes it better than some patterns for piercing, so in a serious pinch, you can work with it.

You won’t have a good time drilling a new hole in your belt with an ax like this, and it’s a little big and unwieldy for jobs like that, but at the very least, you can try.

At least the ax has a feature that makes piercing a potential. I guess the answer is to make sure you keep a knife in your pocket, but it’s nice that the ax has this feature anyway.

Hammering/Pounding/Driving Stakes

The Cold Steel Trail Boss has something that a lot of axes don’t – a flat poll. However, it’s not distinguishing enough to make it a real rarity. There are other axes with this but it’s still a nice feature to have on an ax.

The flat poll means the ax can be used as a hammer, which is useful for driving in pegs, stakes and hardware. You can also use it to drive nails if you need, and it works fine for that. In fact, the extra mass of the ax head makes it quite efficient for that purpose.

Actually, the best part about the ax is that it’s light enough to comfortably wield (as I have said) while remaining heavy enough to effectively drive pegs, nails and stakes.

I will leave you with a word of caution, though. I once had a hardware store hatchet that I used to use to drive steel wedges when I was splitting wood. Never use an ax as a driving tool on hardware if the hardware is comparable in pass to the ax. That is, large nails and stakes are fine, as is anything made of plastic or wood, or anything softer than the ax head.

However, if you use the ax as a striking tool against anything hard, like stone or steel, you run the risk of deforming the poll of the ax, and potentially of deforming the eye of the ax as a result. The hardware store hatchet mentioned is still serviceable, but as you can see, the eye and poll are deformed, which will probably make it harder the next time I have to hang the ax.

By contrast, you can see that I have worn off some of the paint on the poll of the Cold Steel Trail Boss, but it’s not to the point that the steel has been damaged.

You can’t handle it as deftly as a hatchet, but you can still get the job done with it, and considering the fact that the larger size makes it easier to drive stakes more efficiently, that’s a bonus.

Also, how about the fact that you can carve gluts, pegs and stakes with an ax more efficiently than you can with a knife or with most hatchets?

A Generic Note on the “Problem” of Hardware Store Axes

So now that I’ve sang my heart out on the Cold Steel Trail Boss, let’s really get into why it’s such a big deal.

You can just go to a hardware store and get a better one by spending a little more money.

Right? Right?!

Not even close. I, personally, have handled more expensive, better quality axes than the Trail Boss. But not one of them has come from a hardware store. Not one.

Truthfully, my experience with hardware store axes is universally bad, without exception. This ranges from the geometry of the head to the grain of the handle. They’re a mess back to front.

Why is this? Is it because consumers don’t know better? Is it because sellers don’t recognize quality? Or, perhaps, is there a supply-chain-wide cabal of ax-oligarchs that have put their nefarious heads together with the sole aim of keeping quality out of the hands of enterprising consumers?

I’m not sure of the reason, but the effects are clear.

There is a term in the shaving community for a sub-par straight razor. It is called an RSO, or a razor-shaped object.

Ostensibly, such implements look exactly like straight razors.They may even handle like them. However, the moment you apply them to your stubble, even keeping to all other best practices of softening your beard with hot water and adequately lathering, they tear, scrape, and gouge.

In other words, they cannot perform the office of a straight razor because of any of a variety of reasons, primarily because they are improperly honed or made of low-quality steel.

This is how hardware store axes are. They look like axes, they handle like axes, but really, they’re just ax-shaped objects.

Admittedly, I’m not sure about steel quality, but I can talk about grind and geometry. I’ve seen some truly bad quality grinds on hardware store axes that were so blunt they could hardly be used as a maul. That’s remediable, to be fair, but in some cases, the grind is so bad, you’d need an angle grinder to make any headway and remove a quarter of the mass of the tool’s head in the process of restoring an edge.

Again, you can do it, but then you’re doing half of the job that should have been done at the foundry or forge. What are you paying for?

Now, the temper of some hardware store axes is also typically abysmally bad. I recognize that an ax bit shouldn’t be too hard or it runs the risk of fracturing on contact with a hard object, but sometimes hardware store axes are so soft they seem to develop nicks and gouges out of thin air.

The job that these producers do of fixing the ax heads to the hafts is also execrable. I’ve seen hang jobs where I could see voids and air through the eye of the ax. This is not only an objectively low-quality job, it is also unsafe. Failing to displace the wood in the eye against the sides of the ax head’s eye means, frankly, the head is poorly hung and runs the risk of separating from the haft.

In other cases, the actual wedge job is sufficient, but the hang job looks like it was performed by a drunk child. I’ve seen axes where the bit was not indexed in line with the haft, and was torqued to one side, and axes wherein the bit was offset by an angle of several degrees. Not necessarily dangerous, but errors like these definitely rob you of mechanical advantage when swinging.

And now for the worst part: the hafts themselves. There are hardware store axes out there for sale right now with hafts so shoddy they shouldn’t be used as kindling. I’ve seen hafts with grain orientation so bad there was more run out than you could reasonably know what to do with.

I once saw a hardware store ax crack on the first swing. The first swing!

That’s all I can say on the matter, but fortunately, the Cold Steel Trail Boss suffers from none of these problems.

In fact, the most damning piece of all this seems to be the fact that, much of the time you can get a Trail Boss for anywhere between $20 and $40, whereas hardware store axes routinely cost that much or more.

The one advantage you’ll have shopping in store is that you can personally inspect a tool before you buy it, but I’ve gone to outlets where there wasn’t a single specimen on the rack that was worth buying in the first place.

I’ve bought 5 Cold Steel Trail Boss axes, and only one of them had a relatively low quality haft. It wasn’t even that bad, and I have since hung the head on a new haft. In all other respects, they are extremely high quality tools.

Where Can You Get One?

I’ve bought a couple of these Cold Steel Trail Boss axes from Amazon and Midway.com. Both websites periodically feature them at really good prices, between $22 and $30. You just need to be patient, and there are other places you can get them. You might even be able to buy one directly from ColdSteel.com, but if you do, expect to pay more there.

Either way, I don’t need to beat a dead horse about whether you should get one or not. For the price it can’t be beat and it’s still one of the best axes I’ve ever handled, price notwithstanding.

~The Eclectic Outfitter

Thank you for the excellent, detailed overview. This is the exact information I needed to assist with my purchase decision. None of the axe reviews I’ve read have taken this much time to go into each and every aspect of the decision making process in order to make a well informed axe purchase.

Note: buying direct from Cold Steel, frequently offer 25% off AND includes free shipping. Buying axe from other vendors involves extra cost for shipping because of size and weight. Got mine for less than 40$ tax, title and out th door! Excellent article — thank you for th good work …m

Glad you found the article helpful.